Mark Klink.. teacher; sometime artist and occasional programmer... Mark has been and done many things: Swept floors, worked in a factory, been an athlete, a minor government official, a life guard, a computer programmer, and a traditional print maker. For twenty years he taught children and other educators how to use computers. But the thing he likes best (besides family) is making curious pictures. Studied Art at UC Davis and Berkeley.

---

Interview with Mark Klink

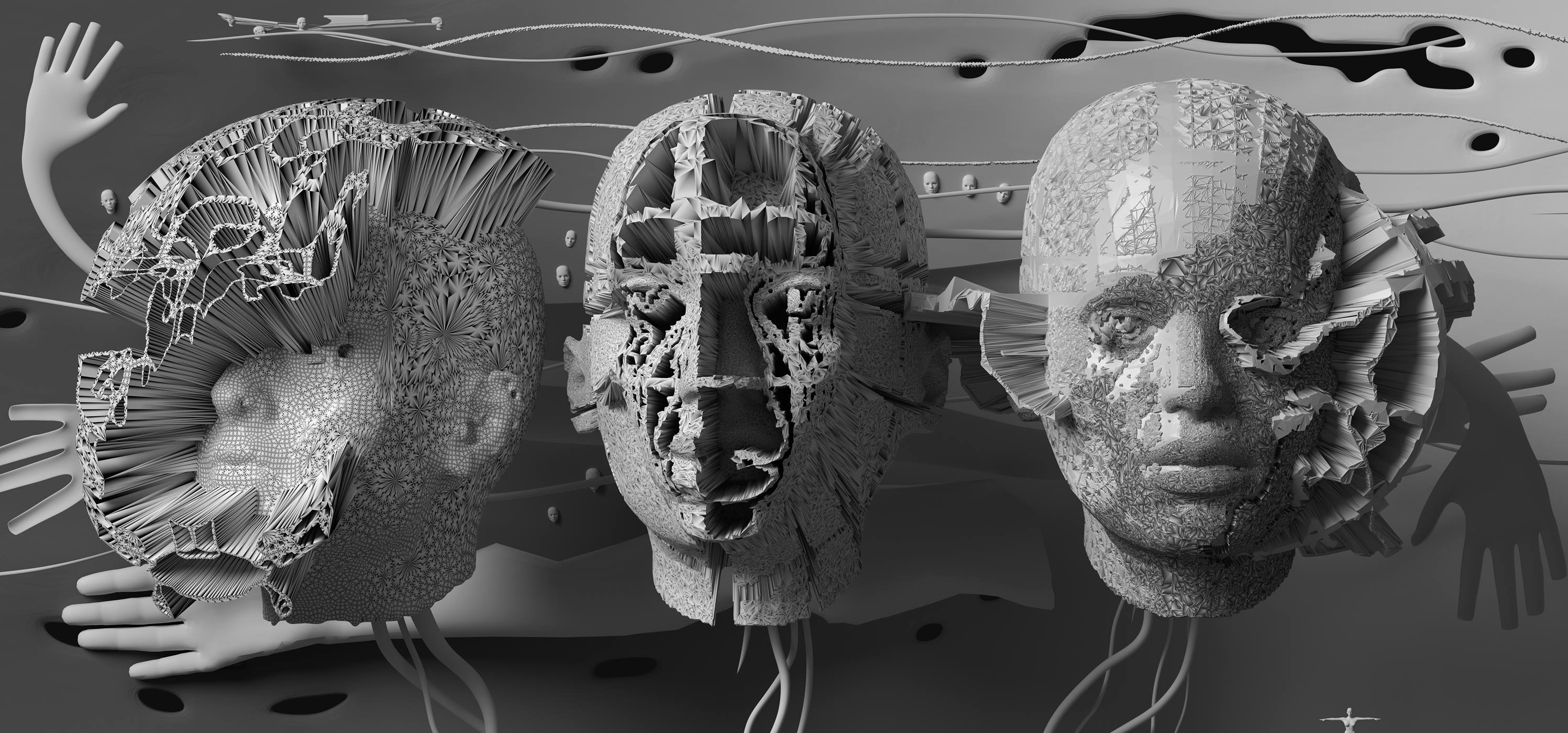

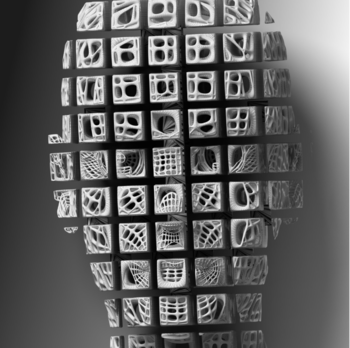

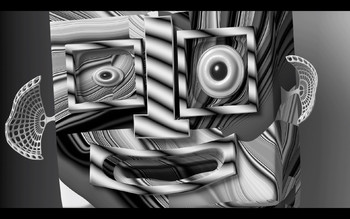

Visual artist Mark A Klink is interested in robots, artificial intelligence, and how we humans handle encounters with the unreal. From his early digital experiments to his current 3D work, he’s focused on manipulating and stretching modern technologies, often subverting them to produce unexpected aesthetic results.

Klink will be bringing some of his recent 3D work to the upcoming CODAME ART+TECH Festival this June, making this a perfect time to catch up with him. I had the pleasure of engaging in a lengthy, enlightening email conversation with Klink over the past few weeks. In that time, we dug into his background as a multi-occupation self-taught technologist and longtime multimedia artist, as well as his reactions to the state of pop culture as it depicts and relates to robots and artificial intelligence, two enduring themes in his work.

This year’s CODAME ART+TECH Festival, codenamed #ARTOBOTS, examines the increasingly tangible sphere of robotics, automation, and artificial intelligence in the modern world. Through 4 days of installations, workshops, and lectures, this conference will showcase developments from the vanguard of art and technology. In this conversation, Klink discusses a few of the questions and themes at the center of this year’s conference, and of his own unique work.

IM: Hi Mark, thanks for chatting with me. We’re really excited to have you involved with the CODAME festival. Briefly, can you start by introducing who are you and what do you do?

MK: I’m a typical bearded, gray-haired geek. Happily married, with a wonderful, successful, adult daughter. I’m fascinated by technology, art, philosophy, literature, movies, nature, people. I spend most of my free time experimenting with digital art.

On your website, you describe yourself as a “teacher; sometime artist and occasional programmer” — how do these occupations work together? How do these different pursuits all inform each other?

I actually retired from my “day job” as a teacher over a year ago! Those three occupations (teacher, artist and programmer) worked together very well. I’ve always considered myself to be a visual artist. Early on, I was fortunate to exhibit my work in various gallery settings. Sometimes I would take a higher paying full time job, then, after I’d saved enough, quit and focus exclusively on my art until the money ran out!

All that changed when my daughter was born. Originally, my plan was to stay home as a house dad, but continue to work on my art. But I discovered that I couldn’t do justice to the two jobs. While some people are absolutely able to focus on a young child and work at the same time, I just couldn’t personally do it, so for a while, I stopped making art. Eventually I began to pursue teaching as a way back into the workforce.

Around this time, I discovered programming. Keep in mind this is during the early 1990s. Most people did not have a personal computer, and only a subset of those people would “go online” by connecting to AOL or Compuserve using a buzzing, crackling modem plugged into a telephone line. In order to complete my studies for my teaching credential I purchased my first computer, a Macintosh LC.

A few years prior, I had encountered a computer for the first time while taking my daughter to a museum. At the side of the exhibit was some early Macintosh, and on it was running one of Rand and Robyn Miller’s early Hypercard-based click and explore games. I was fascinated. Before this I had regarded computers as simply glorified calculators, but now I knew there was more to discover.

So when I got my first Macintosh the first thing I did was to start exploring Hypercard. In short order I became something of an expert with the scripting language it used, Hypertalk. I started making my own Hypercard games, and I taught myself C in order to make code extensions to Hypercard (XCMDs and XFCNs). To my surprise, some of these proved to be very useful for others, and I started licensing them.

Soon, I had several offers to work full time as a programmer. However, I knew that wasn’t really for me. I really only wanted to use computers for fun, to be creative.

So instead, I became a teacher. The great thing was that my school district was unusual in that they staffed their computer labs with fully credential specialist teachers. It was a perfect match for me. I did continue to keep a hand in programming, so I was creating scripts and utilities that saved a great deal of labor in managing the lab and with other tasks.

As much as was practical, I incorporated art in my curriculum. I also continued to explore digital art, and that really took off when I discovered the open source 3D modeling and rendering application, Blender.

What was your early background like? Did you have formal training in fine art and technology, or did you learn another way?

I was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, but my family moved to Sacramento when I was 12 years old. I was very fortunate to attend a high school with exceptional arts education and some impressive connections. For example, before he moved to the Bay Area, pop artist Mel Ramos was the head of the high school art department where I attended school. The teacher with whom I had the most contact, Ken Waterstreet, has work in several major museum collections. All this to say, I was really lucky and had some great examples and mentors early on.

In college, I majored in Art; first at UC Berkeley, then at UC Davis. There was an outstanding line up of teachers at Davis while I was there. Wayne Thiebaud, William T. Wiley, Roy De Forest were among my professors. I think the teacher who was the greatest influence, both in his approach to art and as a person, was ceramics artist Bob Arneson. I was never a ceramicist, but Bob’s playful, thoughtful attitude, his lack of pretense, his openness to his students, and his modesty all impressed me deeply.

When it comes to technology, I’m completely self-taught. In some ways, I feel fortunate about this, because I became involved in tech at a time when things were truly wide open. At the time I began learning, everything felt so new that there could be few “experts.” Anyone with sufficient curiosity and drive could dive into almost any area of tech and, if they performed, could be taken seriously. Certainly some of that continues today. But I suspect we are quite a ways past that raw frontier stage.

How did you begin making art and what influenced you, early on? Were there particular artists or projects that really inspired you?

I have always loved art and loved making art. Somewhere I have a copy of my kindergarten report card in which my teacher notes that little Mark takes great delight in making complex, detailed drawings.

I can’t begin to list all the artists who have influenced me. I want to say the work of every artist I have ever encountered has had its impact. At this point, I feel as though they have all come together in some deep synthesis, so that I can’t single out any one. Whatever comes out of that synthesis is now my own.

When it comes to digital art, specifically, I think the beauty of it is that it is so new. There are no “Old Masters” or “Masters” of any kind who dominate our sense of what is good and what is possible. We are truly free to make this whatever we want.

Let’s talk about the work you are making now. Could you explain a bit about your current creative process? Why you’re making them and what you most wish to communicate?

I’m really interested in the ways 3D objects and scenes can be represented in a file format, and how that can be exploited to create novel effects. Over time, I’ve become more interested in art works that are multi-layered — that work on many levels, aesthetic, ideational, emotional.

I think people started paying attention to my work a few years back when I developed some methods to glitch 3D files.

“Glitch” art — referring to the use of digital errors or corrupted data for aesthetic expressive purposes — has been around for decades. For years, people have been fascinated by accidental glitches, particularly video glitches, that often popped up when early computer systems misbehaved.

Eventually artists began looking for ways to induce those effects. Normally, you take a 2d image file and use an image editing program, Photoshop for example, to manipulate the image. Of course, all image and video files are just long lists of ones and zeros. You can manipulate that data directly rather than using a dedicated editor. Often people will open image files with text or hex editors, then use “find and replace” or “copy and paste” to change the content of the files. That might wreck the file, change it so that it no longer can be recognized as an image.

But if you’re lucky and knowledgeable, the result of the operation might be some strange and unexpected alteration of the image…weird, interesting deformations and color shifts. At this point, Glitch Art may have become something of a cliché. However there are still people deeply immersed in exploring the arcana of file formats and who continue to discover novel effects. There were quite a few prior examples of glitched 3D files, but the specific things I did and the tutorials I posted seemed to have influenced other artists.

The software that we use now to make digital art is so powerful. There are so many controls and options, the permutations and the effects that result are unlimited. It is ridiculously easy to make stunning eye candy, so easy, that our various feeds are overflowing with visual novelties. If you unlock your phone it just comes pouring out. And, just as quickly those images are forgotten, replaced by whatever comes next on your social media feed.

It is far more difficult to make a work of art that requires some deeper consideration, that reveals something new each time you visit it. Making artwork like that is my goal.

Can you talk a bit about the medium and tools you use to create your work? Is there a “most important” tool you use? If so what is it and why is it important?

I use everything I can get my hands on! The most important piece of software, for me, is Blender. It is a complete open source modeler, renderer, video editor, compositor. It even has a built in game engine for interactive content.

For artists interested in experimental 3D, I definitely recommend Blender. There are other proprietary tools that are industry standards when it comes to content production. If that is your goal, that is what you should use. However, I am an open-source advocate.

What about the work you will be bringing to the upcoming CODAME festival — what will we see?

I’m working on a video. It will consist of heavily modified clips from classic (and not-so-classic) movies, tv shows, and documentaries having to do with robots. These will be interleaved with original 3D animations that I’m creating, also involving robots. There will be an interplay between the themes, explicit and implicit, in the “found” video and the animations.

You’re very interested in robots, AI and the nature of consciousness/humanity in your work. Can you talk about this a little bit, as well as CODAME’s #ARTOBOTS theme, what you find important about this theme, how you approach it?

Despite what I said about wanting to make artworks that also work on an “ideational” level, I’m reluctant to say too much. Nevertheless, I’ll say a few things, which should be regarded as vague notions that might, somehow, emerge out of what I’m making.

I’m very interested in our complex and changing attitudes towards “artificial beings.” When they’re not presented as simple monsters, robots (usually humanoid robots) seem, often, to stand in for humans, whose oppression is taken for granted to the extent that they are regarded as some dehumanized other. In fictional situations like these, robots function as a prop within a parable about man’s inhumanity towards man.

We tend to project onto robots the anxieties we have about our own nature and value. Humans have been undergoing a progressive demotion. At one time, we could confidently regard ourselves as the center of the universe, a special creation above and apart from everything else. But, from Copernicus to Darwin, belief in that special status has been continually undermined. The prospect of artificial intelligence draws the curve to its logical conclusion. A corollary to this line of thought is that we humans are, in fact, nothing more than mechanisms.

How do you view recent pop culture dealing with this theme? (For example: Blade Runner, Ex Machina, etc.)

It’s interesting how this has played out in popular culture. The originator of so much of this, of course, is Mary Shelley. Many people have drawn a parallel between the Frankenstein monster and Roy Batty in Blade Runner. Both are the product of a kind of hubris on the part of a creator/scientist. Both confront that “creator,” demanding that he fix what he has broken.

In the Kubrick/Spielberg movie AI, we get another image of robots as exploited and reviled “others.” This is heightened by the pathos of the child robot, “David,” whose love is more intense and pure than that of which any human is capable. This film gives us another take on the issue of “creator vs. created.” The race of advanced robots that revive David at the end of the movie are fascinated by him precisely because his direct connection to their “creators” — the now extinct humans. It is clear, despite their advancement, they are as baffled and awed by the mystery of sentience and creation as we are.

There is another take worth mentioning. I see it , to a degree, in a movie like Ex_Machina. Here the artificial being, Ava, unlike the androids of Blade Runner, successfully escapes her keepers. However, her behavior is very different from Roy Batty, who, at the end, proves himself more humane than the humans who have been hunting him. As his last act, Roy chooses to save Deckard. In Ex_Machina, Ava ignores the screams of Caleb, the human she’s been manipulating, and leaves him to die. Ava is not a monster, but while she can perfectly simulate the affect and appearance of a sympathetic human, there is something essentially alien about her. Apart from the desire to survive and to be unconstrained, her motivation is a mystery.

We see some of this in the robot David in the Prometheus/Alien Covenant movies, who would also destroy his creators. But the best examples of what I am getting at are in the Strugatsky novel Roadside Picnic (the inspiration for the movie Stalker) or some of the work of Stanislaw Lem, which deal, not with robots, but with profoundly alien intelligences and the impossibility of understanding or communicating with them.

We naturally anthropomorphize robots, but it seems very plausible that artificial intelligence could develop along lines that are incomprehensible to humans. That artificial intelligence might be, not necessarily hostile to humans, but, perhaps, utterly indifferent to us.

Ex Machina is a really interesting film. I noticed that many people who watch it get angry with Ava — expecting her to have “empathy” as you put it. Yet, isn’t the whole point of the film that she can’t have empathy because she is a machine and not a human? Even when we know that we’re dealing with a non-human, non-living thing, it’s difficult to change our expectations from a humanoid face.

Yes! We’re “programmed” (an especially ironic — or apt! — term in this context!) to respond to faces. I’m sure that the negative reaction to the closing of Ex Machina comes because all along we’ve been set up (as much as Caleb) to see Ava as a sympathetic human female. We contrast her with Nathan, for whom “others” only exist as instruments, and it’s a shock when she doesn’t behave according to our expectations.

I haven’t even mentioned all the stereotypes the movie plays with: Nathan as the manipulative/genius Silicon Valley CEO type who uses his robots as sex dolls, vs. Caleb as the earnest nerd. Ava might be a manifestation of the deep anxieties both those male stereotypes could harbor regarding women!

Robots and AI do stir a lot of emotions and reactions! Do you think art can help people deal with the transition to a world where we have to interact with both robots and humans — that all look like humans? I wonder sometimes, how human beings will cope with this, emotionally speaking.

I think art does help us adjust to new realities, for better or worse. As individuals, our nightly dreams supposedly help us to assimilate what we encounter during our waking life. I think of movies, and other forms of art, as a sort of collective dreamwork.

I don’t subscribe to the romantic notion of artists as the unacknowledged legislators of the world or antennae of the race. I don’t think artists have any special power or responsibility for leading people in the “right” direction. But, artworks can act as a catalyst through which the audience discovers or creates whatever meaning the world holds.

We may be getting close to the point when AI directed language comprehension and speech become difficult to distinguish from that of a “real” human, at least for mundane interactions. When that happens, I believe it won’t be especially jarring. At some level, we’ll still regard those robotic agents as “un-real” in the same way that we understand that characters in movies aren’t “real.”

I suspect that something as convincing and perplexing as Ava is still in the far distant future. How we will react to that, or how we should react to that, I really don’t know. I suppose we’re just beginning to work on that problem now.